AI Revolutionizes Brain Mapping

In a groundbreaking leap for neuroscience, artificial intelligence is now enabling scientists to map the brain with unprecedented detail. Led by Bosiljka Tasic, a neuroscientist and genomicist at the Allen Institute for Brain Science, researchers have used machine learning to create intricate maps of the mouse brain, identifying over 1,300 distinct subregions. This digital cartography marks a major evolution from traditional techniques, which relied heavily on human observation and interpretation.

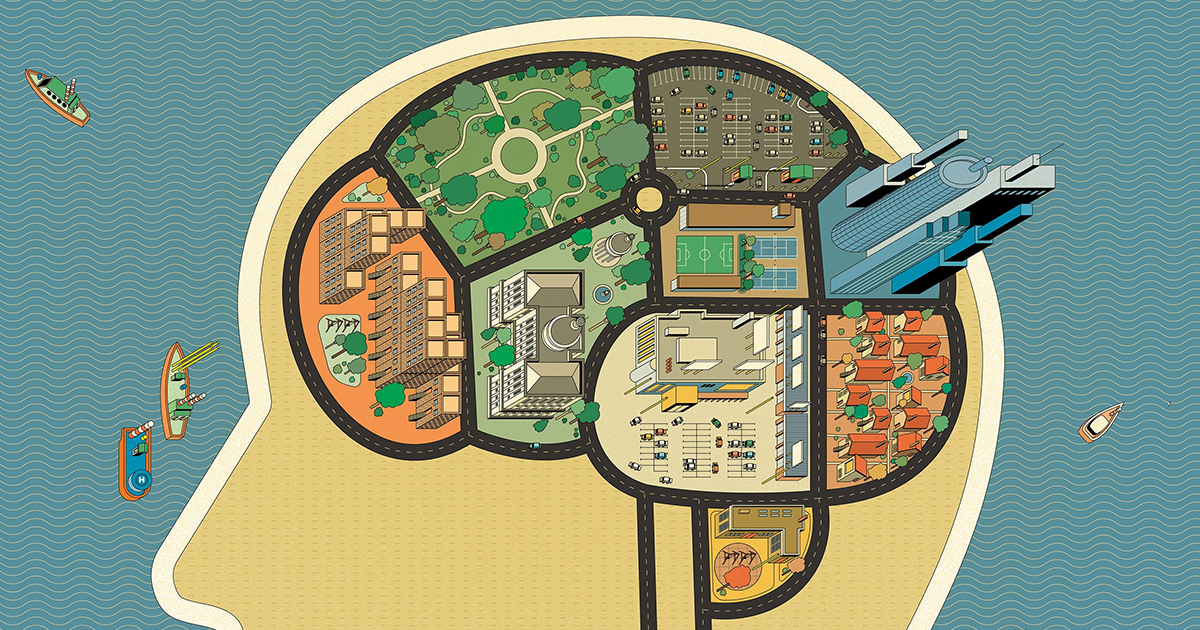

“Location is everything in the brain,” Tasic noted, drawing a parallel to the real estate mantra. Just as neighborhoods within a city have unique characteristics, brain regions are composed of diverse cell types that work together to perform specific functions. Understanding how these cells are organized in three-dimensional space is key to unlocking how the brain operates in both health and disease.

From Brodmann to Big Data

Neural cartography isn’t new. In the early 1900s, German neuroscientist Korbinian Brodmann created one of the first maps of the cerebral cortex by examining stained brain slices under a microscope. This method led to the identification of 52 distinct regions, many still referenced today.

Despite the value of these early maps, they were inherently subjective. Anatomists would often draw boundaries between regions by hand, based on visual differences. Even the comprehensive Allen Mouse Brain Common Coordinate Framework, published in 2020, while based on data from 1,675 mouse brains, still relied on human interpretation to define over 1,000 brain areas.

Modern techniques now allow researchers to investigate cells at a molecular level. By analyzing RNA sequences—messenger molecules transcribed from DNA—scientists can determine which genes are active in individual cells. This method has revealed thousands of distinct brain cell types and has formed the basis of detailed atlases, such as the Allen Institute’s 2023 atlas with over 5,000 mouse brain cell types and the Human Brain Cell Atlas, identifying 3,313 types from post-mortem human brains.

Enter CellTransformer

To transform this massive dataset into useful maps, Tasic teamed up with Reza Abbasi-Asl, a computational neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco. Together, they developed CellTransformer, a machine learning algorithm designed to identify how brain cells cluster into functional neighborhoods.

Starting with RNA data from 3.9 million cells in a single mouse brain, CellTransformer masked the identity and gene expression of individual cells and predicted them based on neighboring cells. By iterating this process millions of times, the algorithm learned the spatial relationships between different cell types and built high-resolution maps of the brain’s cellular architecture.

“We see things that a human eye cannot see,” Tasic remarked. The algorithm could define between 25 and 1,300 subregions depending on the level of detail desired. Even more impressive, CellTransformer produced consistent maps across brains of different sex and slicing orientations, demonstrating its reliability.

Discovering New Brain Regions

One of CellTransformer’s major achievements was revealing previously undetected subregions within known brain structures. For example, the striatum—associated with reward and movement—was traditionally viewed as a single large area. But the algorithm identified several distinct neighborhoods within it, supporting earlier findings by other researchers using entirely different techniques.

Similarly, in the underexplored brainstem’s midbrain reticular nucleus, CellTransformer uncovered four new subregions, each with unique genetic signatures and cell compositions. These discoveries have the potential to resolve long-standing debates in neuroscience where different researchers assigned conflicting functions to the same brain area.

Beyond Mice: Human Potential

While the mouse brain provides a valuable model, the ultimate goal is to apply this AI-powered mapping to the human brain. However, the human brain’s complexity—containing an estimated 170 billion cells—means that scientists still need to gather sufficient data to fuel CellTransformer’s predictions.

“Only if we know how [cells] are organized can we figure out how they can potentially work with each other,” said Claudia Doege, a neuroscientist at Columbia University. Once human-level datasets become available, Tasic and Abbasi-Asl believe the algorithm will be well-equipped to handle the challenge.

Moreover, the team plans to enhance CellTransformer by integrating additional data sources, such as connectivity maps, to provide even more comprehensive brain models. This mirrors how urban planners use both building layouts and transportation networks to understand city dynamics.

Expanding AI’s Role in Biomedical Science

Beyond the brain, CellTransformer could be adapted to map cellular arrangements in other organs. This could allow scientists to compare healthy and diseased states in tissues like the kidney or liver, offering new insights into conditions such as diabetes or cancer.

“I see AI as kind of a helper for the human,” said Yongsoo Kim of Penn State College of Medicine. “Discovery will be accelerated in a dramatic way.”

The CellTransformer project represents a significant step forward in marrying computational power with biological research. As data continues to grow, AI tools like this will be essential in making sense of the complexity of life’s most intricate systems.

This article is inspired by content from Original Source. It has been rephrased for originality. Images are credited to the original source.